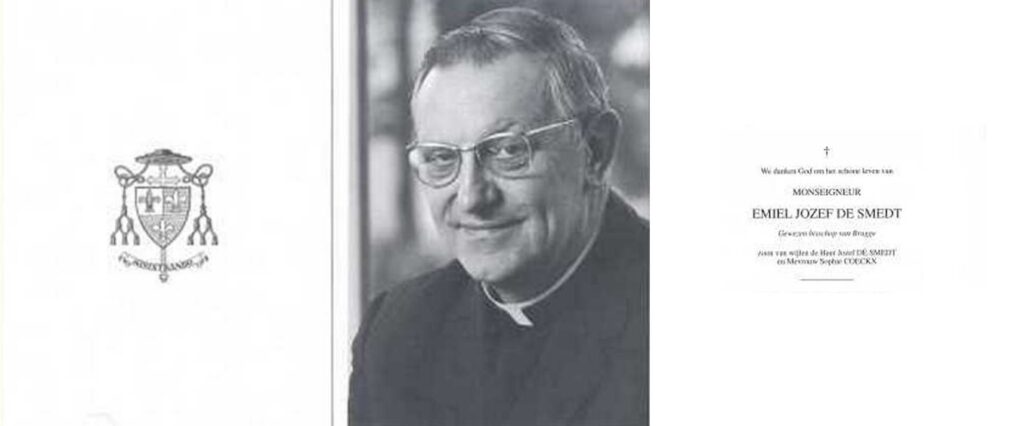

Bishop Emiel Jozef De Smedt of Bruges. Pictured next to him Joseph Leon Cardinal Cardijn.

By Ferdinand Boischot

Emiel Jozef De Smedt was born in 1909 in Flemish Brabant (Belgium) into a wealthy family of brewers. His father was also mayor for the Christian Democrats there for a very long time.

In 1927 De Smedt entered the major seminary in Mechelen and was ordained a priest in 1933. He was then sent to Rome for two years to study, where he earned a doctorate in philosophy and later also in theology. A rapid career followed: at the age of 26 he became a professor at the Major Seminary in Mechelen, in 1938 Regens and in 1940 (at the age of 32!) President of the Seminary - all under Cardinal Jozef Ernest Van Roey and the then Vicar General, the Brussels Léon-Joseph Suenens.

In 1945 - in Belgium, repression raged after the Second World War with a clearly anti-Flemish and anti-Catholic tendency, while at the same time the episcopate was extremely silent and in great fear - De Smedt, at the age of 36, became consecrated as auxiliary bishop for the Archdiocese of Mechelen (since 1961 Archdiocese of Mechelen- Brussels).

Bishop Henricus Lamiroy died in West Flanders (diocese of Bruges) in 1951. Lamiroy had been very authoritarian, reactionary, and conservative towards his clergy and the faithful. He had a strong aversion to socialism, communism and Freemasonry and a great enthusiasm for the French language and for the rich Catholic tradition in France. At the same time he was critical and suspicious of the Belgian policy of compromise and Christian trade union activities.

At Lamiroy's death, the clergy in the Diocese of Bruges was split into very different factions. So, without further ado, De Smedt was piloted from the archdiocese of Mechelen to the diocese of Bruges, while at the same time the path for Suenens to the archdiocese of Mechelen was very elegantly cleared.

The province of West Flanders has always had a particularistic orientation: linguistically, economically and politically. Bishop De Smedt was very well received by the clergy and the people: he was more Flemish than Lamiroy, less authoritarian, closer to the people, very closely linked to Christian Democracy and politics, and showed more interest and goodwill in local customs and outward appearances.

Bishop De Smedt distinguished himself in particular in the expansion of Catholic education and in the fight for its state subsidization, which culminated in the so-called "Schoolstrijd" (school struggle). He made West Flanders the Christian Democratic bastion ( Christelijke VolksPartij CVP ) in Belgium, and this for the next six decades.

Under De Smedt, Catholic social life flourished tremendously with episcopal support and benevolence. The Major Seminary of Bruges developed into the largest seminary in Belgium. De Smedt ordained more than 620 priests in 33 years, including future bishops Johan Bonny ( publicly homophilic), Godfried Danneels (covering up pedophilia and known for his lost and found ring ), and Roger Vangheluwe ( pedophile bishop super-plus).

On the one hand, West Flanders and the Bruges diocese as an isolated Catholic wagon complex and the intensive connection axis between the Catholic University of Applied Sciences of Leuven and the Bruges diocese and seminary will dominate Church life in northern Belgium for almost 70 years.

The close ties between the bishop and diocese, Christian democracy and local politics, the flourishing of Catholic social life, and the major seminary of Bruges contrasted sharply with the rest of Belgium: the Catholic milieu had been steadily eroding there since the mid-1950s (from 1955 the number of seminarians decreased inexorably and sometimes rapidly, except in Bruges).

The Belgian Catholic Christian Democratic Eldorado in the bishopric of Bruges (West Flanders province) was noted in both Belgium and Rome and presented as a pastoral example. Bishop De Smedt thus acquired a special political and religious aura in a country undergoing secularization, especially in Flanders.

De Smedt allied himself primarily with the Christian Democratic Party. In 1958 he had the pulpit proclaimed that "it would be a sin to elect the Christelijke Vlaamse Volksunie ", a rival party.

In 1961 Cardinal Van Roey died and Suenens became Archbishop of Mechelen and Cardinal.

In the same year, 1958 Pope Pius XII died. Cardinal Roncalli became elected as Pope John XXIII. and proclaimed the Second Vatican Council.

Bishop De Smedt was appointed to the preparatory commission called the Secretariat for Christian Unity, although there were few other denominations or religions in West Flanders.

The 1960s were a very turbulent and truculent time for Belgium, both in general and in religious terms.

The Second Vatican Council opened with many expectations, hopes, fears, scruples, forebodings and many dreams and visions - and evidently with no small amount of evil intentions on the part of some participants.

Father Sebastian Tromp SJ, was tasked by Pope John XXIII. with preparing the content of the Council, had carefully worked out a Working plan to keep the whole thing on track.

At the first plenary session of the Council on November 19, 1962, Bishop De Smedt, spokesman for the Secretariat for Christian Unity, took the floor and made an eloquent, fiery speech on the proposed text. He pleaded for the initiative of the Council Fathers and for freedom of thought and speech. The plenary then erupted.

John XIII decided to withdraw the text prepared by Father Tromp SJ.

The Council rapidly became more rebellious.

On December 3, 1962, Bishop De Smedt delivered a fiery criticism to the world public against what he believed to be the "clericalism" and "juridism" that prevailed in the Church. He also very sharply lamented their "triumphalism" (sic). His omissions were widely published in Le Monde, November 4, 1962.

The council went into a torrent: fierce discussions ensued, four "moderators" were elected to calm things down and steer the discussions. Of course, Cardinal Suenens immediately became the moderator and the council went on its bumpy, unfortunate course.

The "squadra belga" (Belgian team) had a very strong influence on the Council in the years that followed.

Not much is known about De Smedt - in contrast to other Belgians (e.g. Bishop André-Marie Charrue of Namur). He was mainly concerned with freedom of belief and pastoral renewal ( "Gaudium et spes"

It is striking that Bishop De Smedt hardly published anything substantial about the Council afterward.

The Council became more and more deadlocked with disputes between two major factions. The papal office was damaged, with the weak Pope Paul VI in particular, painted a pitiful picture. The Council was finally broken off rather abruptly at the end of 1965 and its end was decreed.

At the same time, the political situation in Belgium had become extremely unsettled in these years: a long-lasting economic crisis, high unemployment, the trials and tribulations and deep frustrations of the decolonization of the Congo, the burgeoning struggle of the Flemish for equality and fierce party fighting. The country suffered from high levels of political instability. In addition, in 1965 there was the sudden liturgical chaos, the confusion of the faithful, the escalation of the Vietnam War, the rebellion of the youth and the demand for the grand, noble Council ideals such as the wandering people of God, love, participation, freedom, joy, etc...

Since the 1960s, the Belgian bishops had kept anxious and neutral entirely out of politics.

From 1965, there was turmoil in the university town of Leuven. A Dutch-French language conflict that affected a kindergarten for professors' toddlers triggered nationwide riots and brought Belgium to the brink of a revolution.

The Belgian bishops, led by Suenens and De Smedt, fully associated themselves with the Belgian unitarian political leadership, which wanted to keep the Belgian unitary state.

On Friday, May 13, 1966, forgetting and negating the whole "spirit of the Council" with its noble ideals and bombastic words, they published the armored "Mandement of the Belgian bishops". In military command language they demanded hierarchical obedience of the faithful to the episcopal ordinances.

Flanders was immediately in turmoil.

The government fell twice, in 1966 and 1968. The Christian Democrats suffered huge losses. The first of an as yet unending series of state reforms was initiated.

Church attendance fell by 25% in one fell swoop, and by 75% in the decade that followed.

The Belgian bishops had blasted away the Catholic Church in Flanders in an attempt to save Belgium's unity (incidentally with strong free-spirited Masonic colouring).

Only small scraps remained there after the Second Vatican Council.

(Sequel follows.)

Image: MiL

Trans: Tancred vekron99@hotmail.com

AMDG

4 comments:

For more than a century, the Roman church has been an international gay crime syndicate

As a parochial American, I appreciate the story and the insight given about Belgium.

I was ages 12 to 15 during the Vatican Council and was a fairly bright and curious student of current events.

None of this information was made known to me. All was pictured as sunshine and lollipops at the Council.

Great post, Tancred. Can't wait for the part 2 (and others?)

De Smedt was also a (the?) leader of the Pact of the Catacombs. Looking forward to reading more.

Post a Comment